The LocalHarvest Blog

05 Apr Tue 2016

The 'Unsexy' Side of Farming

Welcome back to the LocalHarvest newsletter.

As a consumer of food, do you ever think about what a farmer has to do to keep their business running and food delivered to your plate? If you do not produce food for a living, could you imagine people relying on you for the food they eat, for their sustenance? Could you envision making your living from what you grow or raise off of your land? Just let it sink in a little that kind of commitment and pressure.

What does it take to be a small to medium-scale farmer or rancher these days? Apart from the obvious of growing high quality food by keeping the pests at bay, controlling weed pressure, improving the fertility of the soil, selecting the right crops or animals for the climate, harvesting them at the peak of flavor (or a little before then), packing, delivering, and selling those crops, there is so much more to it. The necessary but less glamorous side includes financial management, managing employees, paying taxes and payroll, following regulations and obtaining proper licenses, acquiring and maintaining vehicles and equipment, building infrastructure, and the list just goes on. Just like many entrepreneurs, a farmer wears a lot of different hats and must be a master of everything.

As eaters of food, we often just see the farmer or her employee at the market, the food itself, and a bit of the work they do to unload it, display it, and sell it to other eaters. From that vantage point it looks relatively uncomplicated, maybe even something we could do ourselves. The farmer is happy- they are selling the fruits of their labor. The eater is thrilled- they are getting the freshest, tastiest ingredients available and they can feel a sense of contentment knowing their dollars went directly to the farmer. It all feels really good.

What goes on behind the scenes, however, is a lot of tedious, time-consuming bookkeeping, data management, phone calling, emailing, and chasing money. In order to survive, a farmer must pay attention to these things, even if they loathe them. Some farmers use computer spreadsheets, others still use paper and receipt books. Some use the front dash of their truck as their filing system, while others have a cabinet full of folders organized by customer, class, or month. To find and engage customers, there is a lot of phone calling, emailing, and talking in person. There is also social media, print media, advertising, flyering, speaking to groups, and any other method to get the word out. It's simultaneously exhausting and necessary.

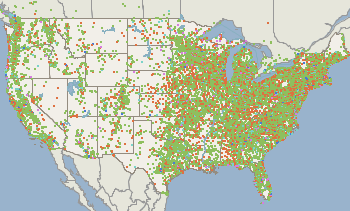

LocalHarvest got its start over 16 years ago to make the lives of farmers a little easier and to help consumers locate and build relationships with the people who grow good food in their regions. That is our core, the farmers and the eaters. To this day, we still don't charge a penny for farmers, markets, restaurants, food hubs, and others to list their business and share their offerings. And we have over 7 million people a year that use our site to locate a CSA, a specific ingredient, find a farmers market, etc. We are making those connections that nourish people and build resilient businesses that sustain families and communities. We are humbled at the power of our small but mighty website to do these things.

Kindly,

-Rebecca Thistlethwaite

28 Feb Sun 2016

Safe Food or Regressive Regulations?

Welcome back to the LocalHarvest newsletter.

Our LocalHarvest staff member John Gethoefer just wrote this letter to his congressman, Earl Blumenauer, regarding the challenges facing small farmers, in particular the new food safety regulations and requirement for food safety certification by many buyers. Once the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) is fully implemented (most farmers have until 2018 to comply), it will be required for nearly all vegetable, fruit, and nut producers to follow these rules and pay for certification. Only those that gross under $25,000 a year in produce sales will be categorically exempt. I can think of no other set of regulations that is going to discourage new farmers from getting started and existing farmers from scaling up than the FSMA rules. The results could be horrific for the advancement of a sustainable food system and do little if anything to reduce deleterious pathogens in our food supply.

Here is an except from John's letter:

My name is John Gethoefer. I am on the staff of LocalHarvest, which is an organization that provides support for small, family farms throughout the US. Congressman Blumenauer's latest email to constituents piqued my interest in regards to "Equitable & Sustainable" agriculture policy. We see first hand every day how difficult the practice of small, local family farming has become in America. It is a commonly felt view among the many farmers that we advocate for that federal agricultural policy usually does more harm than good for small, family farms. In turn, there is growing skepticism among these farming families that any legislation introduced will likely do more harm than good for their livelihoods and viability.

One example that we have seen recently in the struggle to promote local food systems is that large, institutional buyers of agricultural goods typically require vendors and producers to follow the USDA GAP (Good Agriculture Practices) or GHP (Good Handling Practices) standards. We have worked directly with both institutional buyers and farmers local to them and while we have tried to develop training programs that are cost-effective for the farmers, more often than not, the program is too costly for these farmers to adopt. As a result, very few local farming operations qualify to sell agricultural goods to these institutional buyers. While the intentions of GAP/GHP program are to increase safety for the general public, there exists many challenges in terms of equity and ultimately sustainability for the small, family farmers to adopt and therefore compete in the local marketplace.

To comply with the new FSMA rules, a farm has to get each crop certified as food safety compliant. Imagine what a diversified farm with over 10 crops will have to do to certify each crop. The compliance costs vary widely based on how many actions a farm has to take to pass the inspection. On the lower end I found compliance costs of $50/acre up to $13,000/acre if larger infrastructure renovations are required. These include costs such as water testing, testing compost materials, installing deer fencing, building an enclosed packing house, switching to all plastic harvest bins, renting port-a-potties with hand washing stations and the most time-consuming task of endless record-keeping. The record-keeping of organic certification will pale in comparison with food safety record-keeping. Things like daily temperature checks, recording when you pump, clean, and restock your bathrooms, recording when your employees wash their hands, how many deer footprints you found in a particular field, lot numbers for every box of produce you harvest, etc. One farm studied in Vermont had to actually hire a food safety manager to develop all of the plans, implement them, and do the record-keeping (that's a whole other salaried employee on the payroll just for food safety). Like many government regulations, the burdens fall disproportionately on the smaller-scale businesses. A 2010 study (Paggi et al) found a substantially higher GAP compliance cost per acre for small and medium-size operations than for their larger counterparts. It also demonstrated that, extended over time, these higher costs for smaller operations adversely impact a number of important financial variables that can be expected to affect their ability to compete and survive. In plain English, the high costs of food safety compliance and certification could put these smaller farmers OUT OF BUSINESS.

I participated in a mock audit many years back while working on an organic farm in California with some USDA GAP inspectors in training. It turns out those inspectors had no background in biology at all. They literally made up issues on the spot and deducted points from our audit at random. I remember one of the inspectors insisting we cut down a tree that was next to our irrigation well because birds could land on the branches of the tree and then poop on the well head. Even though it was a fully submersible well, they thought that bird poop might somehow make its way into the water. They also pointed out that we had too many hedgerows which may harbor birds and rodents. We told them they were to block dust, wind, and attract beneficial insects and pollinators. They didn't understand those benefits. The last thing they said that really shook us all to the core was that we would have to get rid of the farm dog, who was also our farm mascot. Despite being a gopher and ground squirrel killing machine, they thought she might go poop in some of the fields. In fact, this dog always pooped in the same area and never in the farm fields. We debated between having more rodent pressure in our fields or having this amazing farm dog. How many auditors are out there deducting points or telling farmers they have to get rid of their domesticated animals, livestock, or poison/fence out wildlife in the name of food safety? How about a little common sense and understanding of ecology instead?

If you want to understand more about the Food Safety Modernization Act and who it affects, check out this detailed flowchart from the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition. We need to insist that smaller farmers are exempt from these expensive one-size-fits-all regulations and give them a longer window of time to comply. There should also be whole farm/multi-crop audits that are done in one visit and that certified organic farmers don't have to pay twice for essentially a similar inspection.

Kindly,

-Rebecca Thistlethwaite

28 Jan Thu 2016

Relational Agriculture

Welcome back to the LocalHarvest newsletter.

Local Harvest January 2016: "Relational Agriculture"

One method that smaller scale farmers have used for a few decades to not only solidify their customer base but to also build community and obtain operating capital is through Community Supported Agriculture arrangements. Think about those words for a moment.....

Community, meaning "a feeling of fellowship with others, as a result of sharing common attitudes, interests, and goals". It also means "a group of interdependent organisms of different species growing or living together in a specified habitat". Community is cultivated by fellowship with the people who produce our food and the other eaters in that CSA. They have common interests in eating fresh and healthy, in supporting local and ethical forms of agriculture, in diverting their dollars directly to the producers of the food.

As CSA participants, we are interdependent humans living in a certain region, depending on one another for part of our food, health, and livelihoods. Supported is simple: "to provide for or maintain by supplying with money or necessities". CSAs support both the farmer and the eater. It goes much deeper than a purely monetary transaction. The CSA farmer knows who their customers are, what they like, and how much to grow for them. They also have up-front operating capital so that they have the money to grow the food. They don't have to go to a bank or rely on high interest credit cards. The interest they pay to the CSA customer is good value, incredible freshness and variety, and other values such as exclusive offers, u-pick crops, farm events, experiential education, and more.

And then we have Agriculture: "agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi, and other life forms for food, fiber, biofuel, medicinal, and other products used to sustain and enhance human life". Notice the emphasis on sustaining and enhancing human life. This may be a distinction from some food firms who privilege enhancing profits, building market share, eliminating competition as their main goals. This brings me to the thesis of my article- Community Supported Agriculture is an essential component of a thriving, diversified localized food system and we must continue to support it. As the late Thomas Lyson, professor of rural sociology at Cornell University said, because of the interlocked relationship between the food economy and consumers, people have a civic duty to support important agricultural engagements [such as CSA].

There are many box schemes and food subscription services popping up right and left (see my Food & Tech Disconnect article for some examples) that are not the same thing as farmer owned/operated CSAs and don't provide the same benefits for farmers nor eaters. This is not to say that some aggregated models that assemble foods from multiple farmers, ranchers, and food artisans are bad, indeed they offer an outlet for lots of producers that could be critical for their success. If the service sources locally, pays farmers fair prices, and is clear about their values, then I can get behind those businesses. Just keep in mind the importance and value of a real CSA that is owned and operated by a farmer or group of farmers.

If you want to go further in your relationship and deepen your values of interdependence with your local farmer(s), then consider signing up for a CSA. And do it soon. Most CSAs have their sign-up period in winter and begin providing food sometime in late spring or summer. If you are hesitant about making that big of a commitment, many CSAs now offer smaller shares or trial periods so you can test out their food without taking that big of a financial plunge. If money is a consideration, an increasing number of CSAs are taking EBT or offer other ways to reduce the cost for lower-income people, such as work shares or sliding scale pricing.

With all this CSA boosterism said, I have to admit I am not a member of any CSA because we are able to grow and raise most of our own food. For other items we don't grow, I try to buy as direct as possible because I want farmers to succeed and earn a good wage for all their efforts.

Kindly,

-Rebecca Thistlethwaite

29 Nov Sun 2015

Giving Gifts, Giving Thanks

Welcome back to the LocalHarvest newsletter.

November is a traditional month of completing the harvest and of giving thanks. Thanks to the soil, to the rains, the plants, the animals, and to each other. It also marks the season of rest, when we turn inward for self-reflection, spend time communing with friends and family, repair our bodies (and often our homes and equipment), and make plans for the future. Some go away from their homes during this time to ‘vacate' reality, but I like to hunker down by a warm fire and a good book while looking out the window at the ice covered tree branches. I don't get a lot of time to sit and watch, nor read and self-reflect the rest of the year. When I used to farm in California, I never got this down time. The farm was on all 365 days a year. Now that I live in a true four-season climate, I am grateful for the slowness and forced rest of winter time.

In truth, this year's countless mass shootings and violence around the world have me struggling to find gratitude. I should be immensely thankful for the healthy baby boy that has entered our lives this year, or the new book we wrote together that hit bookstore shelves in June. Our garden provided an insane quantity of huge garlic, grapefruit sized onions, boxes of potatoes, tomatoes, cabbage, plums, and many other crops that we have filling our larder. We have three animals that we will harvest in the next month, so our freezer will be equally loaded. We are healthy, we have a little patch of ground to call ours for the time being, and we have the privilege to live in one of the most gorgeous regions of the country with an amazing community of people. But I can't help but think of all the people who don't have this security, who don't know where their next meal will come from or even where they are going to lay their head at night. There are more people displaced from their homes than any other time in human history- an astonishing 60 million people. How do I tap into joy and thankfulness when I know that is going on? I have to tell myself a different story. I have to live a different story.

As Native American ecologist Robin Wall Kimmerer writes in her book Braiding Sweetgrass, telling a different story can change how we relate to one another and all the beings on this planet. It will teach us the way of gratitude. She says, “One of these stories sustains the living systems on which we depend. One of these stories opens the way to living in gratitude and amazement at the richness and generosity of the world. One of these stories asks us to bestow our own gifts in kind, to celebrate our kinship with the world. We can choose. If all the world is a commodity, how poor we grow. When all the world is a gift in motion, how wealthy we become.”

What gifts will you sow? What gifts will you leave behind? I will focus on writing with integrity and honesty, raising my children with empathy, creating a biodiverse oasis on the land we call home, and being generous with my time to help our community. Small acts of kindness will lead to a world of good.

Cheers,

-Rebecca Thistlethwaite

29 Oct Thu 2015

Eating Through Winter

Welcome back to the LocalHarvest newsletter.

October is harvest season in many parts of the country. Corn, soybeans, wheat, sweet potatoes, winter squash, pumpkins, apples, pears, and many other crops are being harvested right now in a flurry of activity in farm country. Farmers and their employees are working long hours, often into the night, to get their crops out of the fields and orchards. Fall is also a popular time to harvest many livestock species as well, after a summer of fattening up and before the cold winter sets in making the raising of livestock more challenging, if not impossible in some areas.

In my region of Oregon and many parts of the country, farmers markets, CSAs, and farmstands wind down for the season. If you have a garden, you are probably harvesting the last of your crops, perhaps planting a cover crop or a few hardy winter crops like garlic and kale, and calling it good for the year. Yet, despite all these places we procure fresh produce from closing down for the year, WE STILL EAT! In fact, cooler weather often means we eat more, make more home-cooked meals, and pack on a few extra pounds to hibernate for the winter (at least, that is what I do!). However, in all my years of selling meat, eggs, and produce myself, I see this precipitous drop off of demand once the rains or winter weather sets in. Where does everybody go to get their food now?

I'm sure many of your realize this, but farmers have many months of very low to zero cash flow in the winter months. In some parts of the country, it may be 6 months before they see any income coming in, making it very difficult for them to start their next season, let alone survive. Do you make any efforts to continue to support your local farmers during the off season?

A few ways that farmers and communities are trying to partially solve for those 'lean months' are:

- Winter Farmers Markets- more and more communities are setting up indoor farmers markets. Some are still weekly, others are once a month. In community centers, grange halls, schools, churches, and other locations, these winter markets not only help the farmers generate some income in winter but are also a great way for consumers to get out of the house and socialize on what can be dreary, dark, and cold winter days. Look for crops such as frozen meat, cheese, jams, pickled things, winter squash, root crops, onions, garlic, and leafy greens. Some also have grains and beans, prepared foods, homespun yarn, art and crafts. </href="http:>

- "Fill Your Pantry" Events- an increasing number of towns are setting up these one time events in which farmers try to clear out the bulk of their harvest and consumers stock up to fill their pantry, larder, or root cellar for the winter. Often bartering is acceptable, bulk discounts available and pre-orders taken. Think bushels of apples, boxes of potatoes, sacks of dry beans, bulk bundles of frozen meat, and the like. Bring boxes, a cart, and a bundle of cash to these events and "stock up"!

- Winter CSA shares- some intrepid farmers continue to offer CSA shares through winter, or even offer a special winter seasonal share to customers. They may focus on animal products, storage type crops, beans and grains, or other items. I know one farm that does a CSA just in winter with storage crops, eggs, and meat. Other farmers in warm climates like Florida can grow a wider selection of crops in winter than they can in summer, due to excessive summer heat that causes most crops to bolt or wither. Look around in your region- you may be surprised by the variety of winter CSA shares available in your area.

- Other winter events- some farmers do other things in the winter to bring in income, such as hosting workshops, on-farm dinners, barn dances, and other "farmy" events. Pie Ranch in California holds barn dances once a month all winter. We used to offer meat butchering workshops in winter. Still other farms (like Love Apple Farm) offer cooking, canning, and fermentation classes in the "off-season". These can be a great way to connect with your local farmers, enhance your DIY skills, and have fun when there might not be a lot of other exciting things going on in your region.

So as much as possible, given inclement weather, shorter days, busy schedules, and the like, please continue to support your local farmers and ranchers throughout the 'lean months'. Not only does it make for fresher, tastier food for you and your family, but you will help to keep your local food system thriving. Sounds delicious!

Want to find a winter CSA in your area? Search LocalHarvest's directory.

Cheers,

-Rebecca Thistlethwaite

28 Sep Mon 2015

Food and Tech Disconnect

Welcome back to the LocalHarvest newsletter.

Now that I've settled into my new role of LocalHarvest newsletter writer, I thought I should introduce myself. My name is Rebecca Thistlethwaite and I live in the beautiful Columbia River Gorge region on the border between Oregon and Washington. My family has a small farm/homestead of 5 acres where we grow lots of vegetables, pigs, sheep, chickens, and have a few fruit trees. When we have more food than we can eat, we sell or trade it with friends and neighbors. Before this, we used to farm commercially near the LocalHarvest headquarters down in Santa Cruz, California, where we met and became friends with LH founder Guillermo Payet. He was a big fan of our organic meat and eggs that we produced under the brand TLC Ranch.

In addition to writing for LocalHarvest, I teach a couple graduate courses in the Masters in Sustainable Food Systems for Green Mountain College of Vermont and I am the Executive Director of a regional non-profit where I live called Gorge Owned. I also do farm business consulting and have written two books on the subject- the first one is called "Farms With a Future: Creating and Growing a Sustainable Farm Business" (Chelsea Green 2012) and the recent one is "The New Livestock Farmer: The Business of Raising and Selling Ethical Meat" (Chelsea Green 2015). If you are a farmer or aspire to be one day, you may want to check out these books.

In my "spare" time, I like to play with my two kids, trail run, garden, preserve food, read, and volunteer. My dream job would be a professional philanthropist, but in the mean time I just donate time and grant-writing skills to causes that I care about, such as our little community school or school garden.

Now onto the article I wrote for this month!

I'm not a technologist (believer that technology will cure all) nor am I a Luddite (re: all technology is bad). I am writing this article on my laptop with my smartphone nearby while a white noise machine keeps my baby boy in a dependable slumber so I have time to do a little work. Some people, however, think that technology is somehow going to reinvent the way the food system operates or that it is going to magically make it more environmentally friendly, socially just, or affordable to the masses. There are examples of computer tools, such as the amazing LocalHarvest farmer database that connects farmers with consumers, which have made it much easier to find good food. Technology and computer-based applications may nibble around the edges of the modern day food system a bit, but by themselves they won't create a fundamental shift in the system that we've designed in our capitalist society (that is, unless we change or improve on the economic system that we use).

Nevertheless, not only are there a bunch of folks who think technological fixes are going to create an entirely new way of doing business, but they also think they are going to discover some vast untapped pool of money in the local food system for their enrichment. That isn't going to happen either. The food business is fundamentally a low margin business, unless you happen to be in the business of taking a tiny bit of food and sticking it in a large package full of mostly air, like a bag of chips. So I should rephrase, the good food (i.e. healthy, organic, less processed) industry is a low margin business. The fast food, unhealthy, highly processed one probably makes great margins. But we're not so interested in that.

Several startup businesses in the last five years have tried to use computer-based applications to somehow shorten the food supply chain and do away with the weekly trips to the grocery store, farmers market, or even restaurants. They have us believe that us modern day urbanites are too busy for those mundane tasks or shouldn't burn the fossil fuel to do so (I for one believe in social interaction and even having relationships with my food producers, grocery store clerks, and friendly restaurant staff). From the giant flop of Webvan in the early 2000s to more recently the meat subscription service AgLocal, artisan food delivery service GoodEggs (has closed in all but one city), and many other similar models, these efforts have proven to be unprofitable and eventually fold.

Yet we need 'middlemen models' to get food from farm to plate, ethical ones that is. There are some great examples of this, such as computer-based applications like CSAware that assists small farms and CSAs to more efficiently run their operations and act as their own distributors. Like Firsthand Foods in North Carolina that distributes pastured meats for over 90 farmers to area restaurants, paying the farmers premium prices. Or how about Veritable Vegetable (VV) in California that has for over 40 years distributed farm-fresh organic produce to retailers and restaurants around Northern California. VV also pays living wages, is a certified B corporation, and donates a considerable amount of money and produce to charities. There are many other companies out there like this and we need them to thrive. I don't fault anyone for trying to create new business models. As Robert F. Kennedy once said, "Only those who dare to fail greatly can ever achieve greatly."

However, I think there are a lot of lessons to be learned from these business closures that I mentioned above. I will narrow it down to two that I think you LocalHarvest readers might be most interested in.

- Computers don't drive trucks. Turns out that code writers, app developers, and desk jockeys may not be the best suited to creating food distribution companies. Perhaps people who have worked in the industry (say 25 years with Sysco or 15 years with Veritable Vegetable) that are experts in food logistics and transportation should be the ones to lead these efforts or at least be front and center on the management team. Computer technology can only do such much, such as streamlining the ordering and optimizing the delivery routes, but it still won't wash produce, cut and package meat, pull orders, or drive trucks. This quote from Good Eggs founder is telling: "What we didn't fully understand when we started was that we were creating a new category that required a different approach to supply chains, logistics, and commerce - all of the pieces of getting food from local producers to the kitchens of our customers. It was, and is, complicated, way more complicated than we ever anticipated." Yes it is complicated, but thankfully there are many produce, meat, and full service food distribution companies out there that are making it work. Do we really think we can reinvent that wheel (or distinctly tweak it that much)? The real alternative to the food middleman model is the buy-direct-from-the-farmer model (aka CSA), which we know and love.

- Venture capitalists can be parasites. They thrive on quick returns and rapid growth, which is something you rarely see in the ethical food world. Venture capital has not proven itself to be a patient, sustainable source of funding necessary in creating long lasting businesses. I like to say, thank goodness our farmers are not like venture capitalists or we would have nobody to grow our food. Unlike our farmers, they are not in it 'for the long haul'.

Interestingly, in research that I did several years back while working as a social science researcher at the UCSC Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems was that the food businesses that lasted, especially through turbulent economic times, were those that were either privately held (by an individual or family) or cooperatively owned. Businesses owned by outside shareholders did not tend to fair well. They either shuttered quickly (i.e. Webvan, GoodEggs (in all but one city), or AgLocal) because their shareholders were not seeing the economic returns quick enough or they were forced to sell out, oftentimes to a parent company that lacked similar values (i.e. Applegate, Niman Ranch, Cascadian Farm, Seeds of Change, Ben & Jerry's, etc.). Can we build a more sustainable food system when the businesses designed to repair, fix, or reinvent them disappear after only a couple years or if they are subsumed beneath a behemoth multinational corporation that no longer cares about the welfare of the farmers, employees, and other community stakeholders?

I think about the $53 million in venture capital that GoodEggs raised to expand its food delivery model around the country. Or the $1 million that AgLocal raised before it even assembled its management team to market meat to restaurants. In both of these cases they started with a lot of fanfare and were considered "food tech darlings". The investor's money started pouring in. That didn't change the fundamental flaws in their business models and the fact that food margins are slim. As the founder of AgLocal admitted "the novelty of the initial idea didn't pan out". Sometimes it takes good old fashioned reinvestment of business earnings, just like farmers have to do, to build a sustainable, long-lasting business. Imagine if that $53 million instead when to build ten $5 million dollar Food Hubs around the country (akin to the Mad River Food Hub model in Vermont) that served hundreds if not thousands of family farmers to process, package, store, and deliver their food to households, institutions, and food service? Say each Food Hub was owned by the very farmers and food artisans that use its services? That would be a much better use of millions of dollars and create a vastly different food system in which the producers earn equity in the business, are paid fairly, and regionally-based agricultural systems can thrive. That is my hope... .

Cheers,

-Rebecca Thistlethwaite

30 Aug Sun 2015

The Paradox of the Apple

Welcome back to the LocalHarvest newsletter.

Here at LocalHarvest, we think a lot about the concept of local. Local is more than just geography and relationships. It is a statement about how we want to live in an increasingly globalized world. When I recently heard about this story of apples moving around the planet to serve our growing affection for alcoholic apple juice (hard cider) while millions of dollars of domestically grown dessert apples were being tossed out, I thought it was worth exploring. Why is this happening and how could a localized, regionally-based agricultural system rectify it?

In the spring of this year, there were reports of Washington state apples being dumped on the ground to rot because there was more supply than demand for these fresh eating apples and port disputes hampered exports. Problem #1 is excess supply of similar varieties of apples all ripe and ready to be eaten at the same time.

A college professor friend of mine who recently toured a large hard cider factory in Vermont informed me that the majority of apples they use to make their cider actually come from frozen apple juice concentrate originating in China. Not only is the Chinese apple juice concentrate cheaper and available year-round, but this cidery requires such apple volumes that it would have to buy up every single apple grown in New England to supply the demand they have (which is not going to happen). And most apple orchards in New England, just like Washington and the rest of the country, are growing sweet dessert apples for fresh markets, not bitter apples for hard cider or even cheap processing apples. Land, labor, and other inputs are just too great for most farmers to purposely grow processing apples in the US. It is just the culls that go for processing. Problem #2 is the lack of diverse apple orchards in this country growing bittersweet and bittersharp apples for hard cider (they were mostly eradicated during Prohibition). Problem #3 is that our love of sweet and hard apple juice is so great that we import vast quantities of frozen apple juice concentrate from around the globe. The demand is not where the supply is (which is true for many things Americans love from coffee to chocolate).

Thus tens of thousand of tons of domestic apples are being dumped due to oversupply and cheap Chinese apple juice concentrate is coming into the other side of the country to supply a large, nationally distributed hard cider manufacturer. Does this make sense? Why do we simultaneously export and then import the same crops, or in this case, waste crops and then import the same crops? Of course, it would take an entire economics lesson to tease out this distribution conundrum, but I thought at the very least we should be talking about it and maybe taking baby steps to remedy it. How as consumers can we insert ourselves into this socio-economic geo-political board game? Here are my ideas:

- Buy your local apples (and/or other produce) when it is in season. Buy extra to freeze, can, or dry so you can eat it during other times of the year when it is not in season. You can also easily make your own hard apple cider in a short time with very little fancy equipment. Check out this recipe from Mother Earth News here.

- Seek out cideries (or other food products) that utilize local, regional, or at least domestically-grown ingredients. Although LocalHarvest does not sell alcoholic beverages in our online store, many of our producers make hard cider, mead, and other farmstead spirits. If you type in the name of the product into the LocalHarvest search box, many of them will pop up.

- When you buy foods grown in other countries, look for the fair trade, organic, or other social and environmental labels to at least ensure some standards are met in their production and processing. Ideally buy those items that can’t be grown domestically or are not in season here. For me, that would be my daily essentials of coffee, dark chocolate, and the occasional dried mango, vanilla, and other spices. We want you to support good, ethical agriculture and food systems in other countries too.

Even though food has been transported around the globe for thousands of years, it makes little sense to have a system in which we both waste an ingredient and import it at the same time. We can be part of the solution by participating and supporting local and regional agriculture.

Cheers,

-Rebecca Thistlethwaite

Rebecca Thistlethwaite, Farm Business Consulting

Author of "Farms With a Future: Creating and Growing a Sustainable Farm Business",

Chelsea Green 2012 and "The New Livestock Farmer: The Business of Raising & Selling

Ethical Meat", 2015

20 Jul Mon 2015

Love Made Visible

Welcome back to the LocalHarvest newsletter.

It is difficult to look back on the world as it was when we started developing LocalHarvest in 1998 and really remember how different it was. There were only about 500 CSAs and 1,700 farmers markets in the United States at that time. Farmers who did direct marketing had a difficult time finding customers. "Online marketing" was a new concept, and few farmers were wrestling with the dial-up Internet connections common in rural areas long enough to delve into it. And while the market for organic food was growing steadily, the idea of "local food" had yet to take root in the national consciousness.

Things have changed dramatically in the years since. There are now well over 6,000 CSAs, and over 8,000 farmers markets, representing 1100% and 370% growth respectively. While marketing is an ongoing issue in some areas, we regularly hear about cities having trouble attracting enough farmers to meet the sales demand at their markets, and of waiting lists at CSAs. Online marketing has changed too. Sixty percent of the farms in our national directory now have their own website, and a considerable portion do some amount of their sales online. The notion of "local" has become a community value. Good food is here to stay.

I am in a reflective state of mind because at the end of the month I will be leaving my current role with LocalHarvest. It is time for me to put to use a graduate degree I earned some years back, but the leavetaking is still bittersweet. Anyone who gets to work with and for people they admire is blessed, and I have been doubly fortunate because not only do I hold LocalHarvest farmers in highest esteem, but I also have gotten to work with an outstanding group of co-workers. After close to fifteen years with this little company it is impossible to imagine myself leaving entirely, and I hope to stay involved as a close friend of the LocalHarvest family.

Besides having a deep admiration for farmers, I have great appreciation for the people whose commitment to good food keeps farmers in business. It was the need to connect these two groups that brought LocalHarvest into being. Over the years I have tried to use this newsletter to facilitate an ongoing conversation between farmers and their customers. Sometimes I have spoken on behalf of farmers to educate consumers about what it is like to farm, other times as a consumer expressing appreciation to farmers for their hard work. Still other times I have posted calls to action when there has been a regulatory issue requiring collective effort. Many of you have written to me when you have liked or adamantly disliked what I said here. Through this ongoing dialogue we have influenced one another's thinking and the conversation has gone deeper. More than anything else about LocalHarvest, I love the symbiotic relationships the network reflects and supports. Farmers, market managers, chefs, artisan food producers, researchers, and millions of people who love good food all benefit through their connections to one another. All in the name of good food.

Years ago, I used to think it was just about the food. Journalists would ask me why people were drawn to local food and I would tell them that it just tastes better, which is true but it goes beyond that. It also feels better. The bigger truth, as I see it now, is that good food reconnects us to our spirits. When food has been grown and prepared with deep care and attention, we can tell. We recognize it and are drawn to it. When we buy this food from the people who grew it, and talk with them about it, and give our attention to its beauty, we are both drawn more deeply into the center of ourselves, and drawn up and out of ourselves into a circle of connection. This drawing in and drawing out could be called many things. I call it love.

Some farmer friends have a sign hanging in their office that says it best: "Food is love made visible." Yes. For me, it is not going too far to say that love is the driving force behind the resurgence of passion for local food over the last fifteen years. When love reveals itself as food, we respond.

Before I sign off I want to let you know that we are delighted to have found a wonderful writer and former rancher, Rebecca Thistlethwaite, to write our newsletter beginning in August. Having heard her ideas and read some of her writing, it is clear that she will bring new energy and depth to the LocalHarvest newsletter. I think you will be pleased.

Until next time, take good care and eat well.

Erin

Erin Barnett

Director

LocalHarvest

29 Jun Mon 2015

Meet Beekeeper Kari Nobel

Welcome back to the LocalHarvest newsletter.

Beekeeper Kari Nobel loves it when customers approach her at the farmers market to talk about seeing honeybees in their gardens. "It's awesome to hear people being excited about bees!" More and more people are getting interested in bees and even cheer them on when they see them hard at work. Perhaps this is one small upside to bees' well-publicized challenges: bees are certainly no longer taken for granted.

Kari Nobel had not given bees much thought one way or another before she began dating a beekeeper over a decade ago. Now she is fully immersed in their world as she helps her husband Jonathon care for their 700 hives, sells honey at the farmers market and runs their retail operation, which includes a store on LocalHarvest. In the summer, the Nobels and their bees live in Michigan; in the winter they take the hives on semi-trucks down to the citrus groves in Florida. I asked Kari how the work had changed since she first got involved. She said commercial beekeeping now involves much more time-sensitive and high-stakes management of the mites that plague bees and can cause hives to weaken and die. "Nowadays we're constantly on the watch for mites. A bad situation can arise so much faster than it used to." The reason for the change, she believes, is that the bees' overall level of health used to be higher, so they could resist the mites more readily and infestations evolved more slowly. A variety of factors including different use of pesticides now seem to make the hives more susceptible to grave damage from mites. Meanwhile, the mites are getting stronger as they become tolerant of the treatments used to knock them back.

With so many complex and ongoing challenges, it would be understandable for beekeepers to be gloomy. The Nobels, though, seem to draw a lot of strength for the work from their passion for the bees. Kari likens the work to animal husbandry. "Just like a farmer would not want to see a cow get sick, beekeepers care about their bees. We're stewards of our bees, and it's our livelihood. We've chosen this. It's definitely a labor of love."

Knowing that many people are concerned about honeybees' well-being, I asked Kari how consumers could be involved. She said, "The best way to support beekeepers is to make sure you know where your honey is coming from. Honey bought in the grocery store is often imported from Brazil and Mexico. Looking for honey sourced in the U.S. creates a steady demand for domestic honey." Creating a more solid market seems like an excellent way to support beekeepers as they work to make a living under an increasingly challenging set of circumstances. If good, local honey is hard to find in your area, try LocalHarvest!

It will take a lot of work from beekeepers, researchers, and regulators -- and support from the rest of us -- to create a food system where bees can be returned to their former strength and fulfill their role in fully pollinating our food supply. In this, we can take a lesson from the bees themselves. I once learned that a honey bee will make just 1/8 teaspoon of honey in her entire lifetime, and for that small volume will forage for ten hours a day. Yet over the course of the season, a healthy hive will produce well over a hundred pounds of honey. That is a lot of 1/8 teaspoons coming together, and speaks to the power of a common purpose.

To hard work and pulling together, like and for the bees.

Until next time, take good care and eat well.

Erin

Erin Barnett

Director

LocalHarvest

28 May Thu 2015

How will you eat this summer?

Welcome back to the LocalHarvest newsletter.

In many parts of the country the end of May marks the beginning of the local food season, and with it come many delights. Bringing home greens harvested just hours ago is exciting after months of shipped-in produce. After being snowbound all winter, it is just as exciting to see neighbors browsing at the farmers market, and the friendly, familiar faces of your local farmers. Late spring is a time of anticipation and reconnection for local food lovers.

The excitement of Spring inspires many of us to want to upgrade our eating habits in some way. This requires some consideration and thought, since changing our eating patterns takes intention and planning. Changes we might consider include shopping a farmers market or farm stand, setting aside more time to cook, redistributing our budget to create a little more money for food, and/or incorporating more fresh produce into our meals. Creating an intention for the new growing season essentially means spending time asking ourselves how we want to eat this summer.

Once we have committed to an idea, the next step in making it happen is putting structures in place so that the change is doable. The plan depends on the goal, but in all cases it is useful to make the plan as specific as possible. "Shop at the farmers market more" is not nearly as effective as "Stop at the farmers market every Tuesday on the way home from work."

Many of us have a general goal of eating more local food. Unless this goal becomes specific, though, it can feel either overwhelming or unmanageable. Fortunately, there are a variety of organizations that offer opportunities to help people jumpstart changes to their food buying habits. My local food co-op offers a 10 day "local food challenge" twice a year, and there area many of these nationwide. For many people, short term commitments like these are a good way to get started eating local or to take their commitment a little deeper in some specific way. Most local food challenges focus on the amount of local food consumed, but Michael Olson of Food Chain Radio offers a different angle. He calls it the "2 x 2 Pledge." The commitment is pretty simple: spend $2/day on local food, and convince two other people to do the same. One thing I like about Olson's idea is that it is so easy to measure and feels so doable. I can do $14/week without either breaking the bank or feeling overwhelmed. The other thing I am drawn to here is the potential cumulative impact. If a few people took the pledge and got two other people to sign up until eventually everyone in my town (population 20,000) signed up, together we would add about $1.5 million to the local food economy per year. Olson says that local food dollars recirculate seven times before leaving the community, meaning that our $1.5 million would have a $100 million impact on our local economy. Over time, that kind of money - and the energy it would generate - would utterly transform our local food system. It could happen here, and it could happen in every town and city across the country.

All of our efforts to upgrade our eating habits have the potential to make a big impact in our lives and in our communities. As the new growing season gets underway, we at LocalHarvest encourage you to spend some time thinking about how you want to eat this year. What's your intention and how are you going to make it happen? Please share your ideas! We love to hear from you.

Until next time, take good care and eat well.

Erin

Erin Barnett

Director

LocalHarvest

30 Apr Thu 2015

Living the Drought

Welcome back to the LocalHarvest newsletter.

The drought in California has been in the news more lately as the state groans through its fourth dry year. The situation is indisputably urgent, and personally relevant for just about everyone who eats. Last week I realized I was having a hard time imagining the situation because it is inconceivably big, so I decided to start small. I called Linda Butler, a farmer from Lindencroft Farm in Ben Lomond, CA. Within minutes, the drought became much more real.

As a small-scale farmer with no access to municipal water and no water rights, Linda and her husband Steven are living the drought day in and day out. They own 90 acres of sandy soil on a hillside in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Ten years ago when they bought the property, they terraced two acres to carve out a small farm. In the beginning, rain was plentiful. "Back when our valley got 60-80" of rain a year, everything thrived," Linda remembers. "We would lay a heavy layer of compost over everything, and count on the rain to do the rest." The Butlers rely on their well and two reservoirs for all their water needs. Before the drought, the winter rains filled their reservoirs, replenished the well, and watered their winter crops, allowing them to save the well and reservoir water for summer and fall.

Last year they got less than 10" of rain, Linda says, and had to irrigate through the winter. The well level is now precariously low and not refilling. The farm is different. The Butlers no longer grow water-intensive crops like melons, and have stopped watering their roses and other ornamental plants. Fruit trees get watered first. Vegetable crops now get a time-consuming six inch layer of straw mulch to help conserve moisture. Linda says they are "growing less but working more." Even the types of insects that come to the gardens have changed.

Last year the Butlers took money out of savings to buy water from a neighboring water district. This year there is no water to buy. It was too expensive anyway. "Last year we said to each other, 'this could be our last year.' We are saying that this year too."

Every choice comes down to water. Until recently, the Butlers sold their produce to local restaurants and to local families through their CSA. This year they closed down a quarter of their farm because they couldn't water it all. That meant they had to drop their restaurant accounts. They miss the income. "We try really hard to keep our employees employed, but boy is it tough. If our car breaks down, I don't know what we are going to do."

Despite the daily strain and worry, Linda remains hopeful. "We will get a decent winter one of these years. Then we could build another reservoir and we'd be okay. That's my dream." Until then, Linda says that they will continue making do. "We find that we are willing to give up more and more and more. We don't go on vacations or to conferences anymore, but it doesn't really matter. Our farm is where we want to be. In spite of everything, I think it's the most beautiful thing we have ever done with ourselves."

Since talking with Linda, I have been thinking about the drought every day – about the many present and future hardships of growing food; about how easy it is to take abundance for granted. Mostly I have been considering the resilience of the human heart, which has the capacity to love a life this difficult, and does.

Until next time, take good care and eat well.

Erin

Erin Barnett

Director

LocalHarvest

30 Mar Mon 2015

The only work there is

Welcome back to the LocalHarvest newsletter.

Last summer one of my country neighbors told me a story about another neighbor's barn cat who decided to have her kittens in my neighbor's shed. A couple of months later, one of the kittens fell from the loft and lost use of its back legs. When the mama was ready to move the litter back to her home farm, the lame kitten was too big to be carried and had to be left behind. Every day after, the mama trekked a half mile across the fields to tend the lone kitten. This had been going on for some months at the time I heard about it. When I told my daughter the tale, she said, "Awww! The mama loves that kitten a lot!" I don't know if cats can love, but this story makes me think about how we creatures of the Earth occasionally make a choice driven by something more reliable than love and deeper than reason. If everything within us tells us it is the only thing to do, we do it, despite the strain and risks involved.

For some people, farming is like that. Whether or not it pencils out, it is the only thing they can imagine themselves doing. It is the only work there is. Last week I had the pleasure of talking to with one such farmer, Carden Willis, of A Place on Earth CSA Farm in Turners Station, KY, about 40 miles outside of Louisville. Carden and his wife Courtney run a 50-share CSA. When they arrived on their farm eight years ago, the soil was worn out from hard use in tobacco production and the only structure on the place was a dilapidated barn. The early years were devoted to rehabilitating the land and putting basic farm infrastructure in place. Then their two boys came along, now four and two, and since then much time and attention has gone toward the children. Between the farm, the boys, and Courtney's full time teaching job, they have their hands full. "My goal for the last four years has been to survive, and so far so good with that," says Carden. But farming while parenting full-time brings considerable challenges, and Carden allows that he has done "an awful lot of farming by headlamp" the last few years.

Yet they persist.

Before the idea of becoming a farmer came to him, Carden says he just hadn't seen a way to feel good about working any of the occupations he could imagine. Farming suited him completely. "With farming I was able to find something that addressed the central, whole parts of myself. I can be challenged mentally, physically and psychologically. Whereas it was a great stretch to see myself working in a job. So as long as I can farm, this is all I can see myself doing."

It would be easy to overstate the impact of this certainty and believe that it would make farming easy. Yet singularity of purpose does not dig the potatoes, or lengthen the day, or pay the bills. The work itself remains full of struggle and compromise. Knowing this is the only work for him doesn't necessarily infuse Carden with perfect confidence either. He spoke to the difficulty of expanding the size of the CSA while the boys are small and their needs must sometimes trump the vegetables'.

Carden's certainty about his work doesn't assure him that he can do it, only that he will. That knowing seems to offer a kind of protection against the doubt that might otherwise gnaw at the edges of a proposition as complex and enduring as small-scale farming in the modern world.

As farmers everywhere head into the greenhouse and the fields this Spring, it is my hope that all will be blessed with the gift of deep certainty about their work. And may the rest of us support our local farmers all season long with gratitude for the purpose and perseverance they bring to the work of growing good food.

Until next time, take good care and eat well.

Erin

Erin Barnett

Director

LocalHarvest

02 Mar Mon 2015

John Ubaldo, on 'doing it right

Welcome back to the LocalHarvest newsletter.

In our last newsletter, LocalHarvest president Guillermo Payet reflected on the last 15 years in the local food movement. Several people commented on his article, including one John Ubaldo of John Boys Farm who felt that small scale farmers should talk up their strengths. "We have a lot more power than we are given credit for," he wrote. I was intrigued by this idea, so I looked him up and was entirely taken by his description of his farm, and by his photo. Anyone who looks equally comfortable carrying a piglet and a baby is somebody I want to talk to.

My hunch proved right. I like talking to all farmers, but the fiery ones might be my favorite and John is all fire. Exhibit A: "One of my jobs at the farmers market is to beat people over the head about how much work actually goes into farming. Most people have no idea! I've been doing this for a long time and I'm still staggered by how much work goes into doing it right. People have to get that. You have to be willing to beat people up."

"Doing it right" is one of John's catch phrases, and you get the idea that there isn't much wiggle room between right and emphatically not right. He never sprays anything on his crops, even organically approved products, and he gets even more "angry and militant" (his words) about GMOs. In short, he's a purist about producing the highest quality food, and a purist who takes his role as a health educator seriously. "Small farmers are in a is a powerful position because of our ability to impact people's health. How many other jobs offer the ability to change people's lives so positively, on such a basic, human level? Not many. That's not something we farmers can squander. If we do, we're idiots!" There's that fire again.

John wants customers not only to pay whatever he asks for his products, but to thank him afterward. And it seems they do. "I am not the only meat guy at our farmers market, but mine is the only stand with a line. If you're doing it right, your products are going to set themselves apart. Telling the story about what your farm does gets people excited about your food, and then people from all walks of life choose to eat properly and are willing to pay for it."

When talking with his customers about their food choices, John will sometimes go dollar for dollar with them comparing the cost of taking the family to McDonald's versus what they could get for the same money at his stand. "I'll tell them that the main difference, besides their health, between fast food and my food is convenience. I'm not afraid to call people out on being lazy. At the beginning, it was tough sell, but now, every week they're there, and they eat what we bring down." His style wouldn't work for everyone, but it seems to work very well for him, perhaps because he does it with so much heart. "The way I see it, I have hundreds and hundreds of family members. We do a lot of education and we find out what our customers are cooking at home. Then they are either talking to me at the stand every week, or avoiding me because they are doing something stupid and don't want me to bop them."

I loved this John Ubaldo character, and if I ever find myself in his neck of rural New York you can bet I'm going to look him up. Meanwhile, I am taking his words to heart. Farmers who produce good, clean food should be extraordinarily proud of it. And maybe the rest of us could raise the bar a little higher in our food choices and move a little closer to our own version of "doing it right."

As Guillermo mentioned last month, 2015 is LocalHarvest's fifteenth anniversary. We are going to devote most of our newsletter space to our members' voices this year. We created LocalHarvest to serve farmers, and this year we want you to hear directly from some of them, like John Ubaldo. If you have topics you'd like our farmers to weigh in on this year, please submit your ideas via our comments page.

Until next time, take good care and eat well.

Erin

Erin Barnett

Director

LocalHarvest

01 Feb Sun 2015

15 Years of Good Food

Welcome back to the LocalHarvest newsletter.

Fifteen years ago this March, we launched LocalHarvest.org, and this month I offered to be the guest newsletter writer so I could share some thoughts on the "good food movement."

Back in 2000, the organic food movement was well established, but many people, including me, thought that it was starting to lose touch with what we saw as its true 'essence.' We wanted a food system that went beyond the "no synthetic chemicals" imperative of organic to create a food economy that existed on a more 'human' scale. We hoped this movement would create structures that renewed local economies and environmental health, strengthened our communities, and led to the mindful enjoyment of sharing fresh and delicious foods with our loved ones.

At that time we hoped that by redirecting the conversation to include local food, we could take back the 'good food' flag from the money interests then starting to take over the organic market space. We wanted to return it to its legitimate grassroots owners: the small farmers, CSA subscribers, farmers markets, and myriad small businesses working hard to create food systems based on quality, authenticity, fairness, and environmental responsibility. We joked that the day might come when 'buy local' would be trendy and if that happened, real CSAs would have to defend their businesses against franchised CSAs or other inauthentic attempts to capitalize on the demand created by good, honest food.

That day did come. We now have dozens of venture capital-funded enterprises trying to capitalize on local food, farm to table, and other permutations of the good food movement. But who is benefiting? Unfortunately, in many cases, it is not the farmers. The reality is that handcrafted, sustainably grown food is expensive to produce and in most cases cannot compete against conventional agriculture on price. The margins on good food are so slim that companies cannot both pay farmers well and create the kinds of returns on investment that traditional investors expect. Fortunately, there are now other "patient capital" options, like Slow Money, that will fund food businesses without unreasonable expectations of large liquidity events. We believe that these sources of funding are essential to the health of the good food space.

At LocalHarvest, we believe that for local, sustainably grown foods to become more than a niche market many things still need to change. Energy prices need to reflect their true costs - including their environmental costs. The very fabric of our culture needs to change so that more people have the time and resources to choose their food with considerations of community and quality in mind, rather than exclusively by convenience and price.

Cultural changes come slowly. We are aware that this is a generational change that we've embarked on. The groundwork has been laid, however, and we feel hopeful about the continued changes that the next 15 years will bring.

Guillermo Payet

President

LocalHarvest